Sadly we can’t put video up here now. But meanwhile you can check it out on Vimeo.

It’s been worth the challenge of early rising to go the Moreland Station Waiting Room to see people enchanted with the worms (early birds and all that). Those early morning commuters are the most enthusiastic visitors to the waiting room. Lots of great conversations, more tips for worm farms and composting from them and we try to give a few to people new this whole world.

Alex and James haven’t (yet) gotten into worms but the attraction is clearly there…so watch this space.

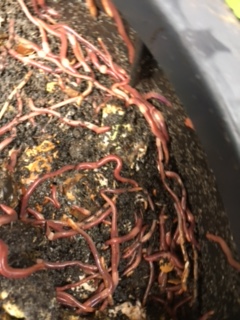

Francis has a worm farm already but has had the same experience as us, sometimes they flock (do worms flock?) to the top and don’t shy from the camera and sometimes they burrow down (we all hope that’s where they are). Maybe someone can explain this over the next few weeks–there’s some pretty experienced wormy people in Brunswick. Francis loved the castings our worms provided–it’s so rich and generous!

And then there was Sophie–I think she was feeling the joy of the worm portraits! As we watched the mesmerising worms in the video together, our conversation drifted from worms to gardens to cats. We’re both entranced by the way that once you enter the world of animals (that special moment when they let you in) you have to respond to their timeframe, as we did with the worms who don’t turn up to be photographed at our convenience — we had to wait. Watching the worms eating the shreds that we’d recycled yet again from an earlier art project, Sophie told me her own shreds art adventures.

Maria and I have a work in MoreArt at Moreland Railway Station Waiting Room…co-composed by us and our worms, with musical contributions from Jim Denley. It’s called Waiting. We’ll be posting more on the ongoing process, but meanwhile, here’s our blurb:

Waiting is a collaborative art work, co-composed by us and worms. In this composting collaboration we feed the worms what we are eating and they transform ‘dead’ matter into live soil, providing us with castings and with food for thought. We were drawn to work with worms when we sensed an affinity between our commitment to recycling and their composting/transformational skills. Worms still retain much mystery, at the same time as being a common—though often unnoticed—part of everyday life. Waiting and listening are our methodologies. Working with sound and video in a series of short diary-like pieces we attune to the worms through listening to the sounds they make and amplifying them through our own bodies.

No worms are harmed in this work.

The video plays weekdays 7-10 and 4-8pm , with sound playing in between. Weekends it’s video 8:30-12 and 4-9pm, with sound playing in between. Unless gremlins come in and turn off the power.

, with sound playing in between. Weekends it’s video 8:30-12 and 4-9pm, with sound playing in between. Unless gremlins come in and turn off the power.

We’ll be there to open the gates and invite people in to wait with us on Monday morning, November 27, and in the evenings on Thursday November 23 and Saturday December 9 for the evening bike tours — and intermittently even more, to check up on the gremlins.

At the same time as we’ve been looking after our installation, Waiting, (more on this in a separate post, but meanwhile I can’t resist a couple of spoiler alert images), I came across something very unexpected… an academic journal paper that is actually a guide (“Compost Politics: Experimenting with Togetherness in Vermicomposting”). I was lured in by the way Sebastien Abrahamsson and Filippo Bertoni write about composting as a practice, a process, an enacting of relations of togetherness. That struck a chord – what they do as ethnographers—making/thinking wormy compost bins—resonates with what we’ve been doing as artists. And with many of the same experiences, including thinking about slowness and spaces for hesitation as well as sensing the precarity of co-compositions as you try to find what worms like to eat. And in those slow and hesitating spaces (for us, spaces of waiting), a particular sort of knowing emerges: “Knowing emerges in vermicomposting… as a set of practices, multiple and contingent. In other words: you may not know, but rather become attuned to your worms.” (133)

Attuning to your worms… another chord struck there. For Abrahamsson and Bertoni attuning meant “learning to speak worm” through the language of food – “a language shaped not in the mouth but through guts.” (134) And with this learning and speaking came the ‘togetherness’ of decomposition—an assemblage involving the worms’ guts, the flora and fauna inside the bin, the whole apparatus of the worm bins, the practices of feeding and the eating habits of all involved…

Even though I’ve been reading all sorts of guides along the way in this project, I really like the way this one brings together practices and politics at the most wormy every day level. And the way it offers some great tips for maintaining our wormery (grind those eggshells more!). Added bonus — it’s a freely downloadable PDF.

Yikes, it’s been months since my last blog. I’m not sure what I’ve been doing – I seem to have been in my own winter hibernation, unlike the worms who have been chomping away.

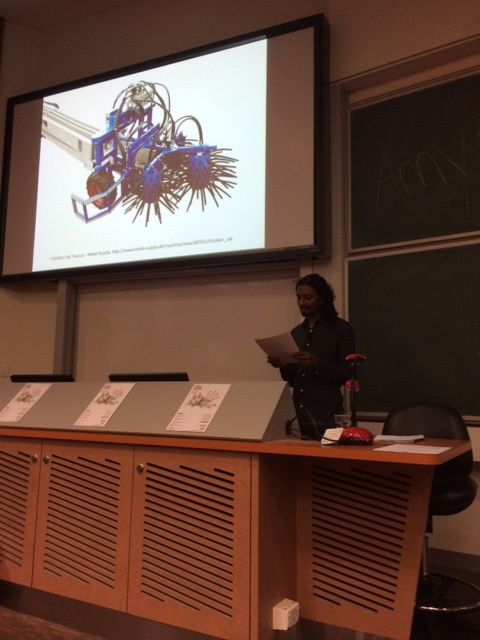

There’s a post that I’ve been meaning to write for months – from the Animal Studies conference in Adelaide back in July. It was another wonderful Australasian Animal Studies event, with so many great art works and presentations, though sadly worms didn’t really feature. Anyway, the one paper that I’ve been thinking about for months is Dinesh Wadiwel’s “The Werewolf in the Room: Animals and Capitalism.” I was drawn to Dinesh’s session by his question in his abstract: “What happened when anthropocentrism shook hands with capitalism?” I liked that he began by asking what animals see when they confront the machines of capitalism and his answer – a werewolf – a being with a voracious appetite. Dinesh evoked labouring animals as political subjects rather than as objects. And if animals are labourers, producers of value, the question of their working conditions comes up. And with it, the issue of time and their need for time away from the harness of production – like any worker.

Speaking of the harnessed to the job, here’s Dinesh and his image of a chicken harness

So in this era of intensive factory farming, as activists, we could try to address animals’ working conditions, suggested Dinesh. I was stunned by the logic and acuity of his argument – while we hope (and work for a vegan revolution), in the meanwhile, this could offer a viable and unexpected strategy, and unexpected is always a good way to go. And I have to say, it was really exciting to see capitalism back in the discussion like this.

For the last few days, I’ve been deep into Donna Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene and I’ve been excited by how she revels in the “wormy pile” that is compost (32). I like to imagine that she would feel a-kin to the squirmy companion critters in our compost bin—even if worms don’t actually loom large in her writing. Speaking of compost, I love how in this book Haraway proposes compost and companions as more congenial figures for kin relations with critters than posthumanism. I’ve never really warmed to posthumanism myself, preferring new materialism and the more-than-human (if we want to bring human into the fore/background) and now I’m thinking about how Haraway’s ‘com’ figures also evoke the with-ness of kinships.

So I decided I needed to go back to Haraway’s earlier book, When Species Meet, where she digs into the roots of companion and finds cum panis–with bread (17). This reminder of how breaking bread and eating together lie at the heart of companionship makes me notice how our worms, companion-critters, eat with us. As I put my breakfast makings and leavings into the worm café and compost bin, I realize that it’s not just that we are feeding the worms but that they are actually eating what we eat—we are all eating the same food, drinking the same drinks (yes, an incredible amount of coffee and tea and quite a lot of toast, speaking of panis). A moveable, shared, companionable vegetarian feast.

As I drink my/our morning coffee and munch my/our toast, I remember, too, that Darwin also recognized worms’ companionability, their sociability: “They perhaps have a trace of social feeling, for they are not disturbed by crawling over each other’s bodies, and they sometimes lie in contact” (15). Or, as Donna Haraway might put it, “entangled meaningful bodies” (26).

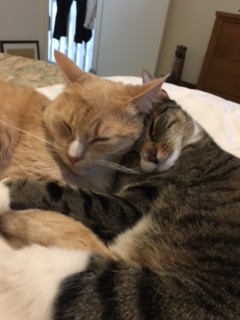

Ok, I can’t resist bringing Z&Z into this conversation. Again, they are still in bed upstairs while we’re all having breakfast downstairs and outside (yes it’s still wintry cold here). But as ever, Ziggy and Zazie are part of this assemblage and have a lot to say about companionable entanglements.

In an earlier post, I was thinking about how Haraway reacted to Deleuze and Guattari’s ‘becoming-animal.’ It’s not that she rejects becoming, it’s just that for her what matters is real worldling becoming with. And the care and curiosity this involves. In When Species Meet, she talks about “practices of care” (90) that shape all the critters in the relationship—and the need to “act in companion species webs with complexity, care and curiosity” (106). Her com or with figures resonate with Vinciane Despret. As I’ve been reading their books together–and together with the worms–I’ve loved how they write with a certain attuned entanglement with each other and with animals—sharing interests and concerns and questions and surprises: “Emphasizing that articulating bodies to each other is always a political question about collective lives, Despret studies those practices in which animals and people become available to each other, become attuned to each other, in such a way that both parties become more interesting to each other, more open to surprises, smarter, more ‘polite,’ move inventive… partners learn to be ‘affected’; they become ‘available to events’; they engage in a relationship that ‘discloses perplexity.’” (207)

Lots to chew on there! Before I finish my last coffee and piece of toast—spoiler alert—I want to mention some more com relations, that I’ll add to the compost of my next post where I want to think about the complex kinship of working with worms in an art project as collaborators, colluders, contrivers.

No, it’s not really a can – just another of our compost bins – but there’s lots of proximate wriggling, not to mention putrefaction and fermentation, so I’m putting it up anyway. Sadly my version of WordPress doesn’t like video and turning the movie into a jpg was a can of worms in itself so please use your imagination here…

Ok, now that thanks to Darwin I’m thinking through intimacy with the worms, it’s time to open the can of worms that is ‘becoming-animal.’ Will becoming-animal help think/work with the worms? Will they help think/work with it? Becoming-animal is one of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s many becomings. Like so much of D&G’s work, the concept is purposely slippery, or can I say wriggly? Anyhow, I do like how it seems to vibrate somewhere between or beside the literal and metaphoric. Time to get down and dirty with D&G, but spoiler alert, it can be a bit soupy.

D&G are trying to get away from ontological states of being here. They talk about becoming-animal as movements by contagion, as a way of thinking movements that are not about the more familiar relations of pity, identification, analogy, imitation, representation, resemblance, or reproduction. In this Spinozan vein, they are invoking forces and “a proximity ‘that makes it impossible to say where the boundary between the human and the animal lies’” (273). That works for me. And it works even better when digested by Christof Cox, who takes philosophy into wonderful artful and sonic zones. Cox reckons becoming-animal is being “drawn into a zone of action or passion that one can have in common with an animal. It is a matter of unlearning physical and emotional habits and learning to take on new ones” (23).

From Cox, I sense becoming-animal as entering (should I say worming into?) a shared affective and productive zone to experience common capacities with animals rather than imitating their forms. And in this movement, he explains, we can experience new physicalities, new emotions, and new relations with others and with the world. I feel inspired by Cox’s approach. Moved as it is by engaging with artworks, it sidesteps Deleuze and Guattari’s abstraction. Perhaps in this way Cox helps rescue becoming-animal from what Donna Haraway criticizes as D &G’s “disdain for the daily, the ordinary, the affectional rather than the sublime.” (29) And hopefully the worms help too — what could be more ‘daily’ and ‘ordinary’ than worms– as we work together, connected by affect and affection?

Cox’s focus on artworks and his idea of unlearning/learning anew reminds me of the work of Melbourne-based artist Catherine Clover. I love her play with voice, listening, unsentimental relations with birds and lots more that I’ve written about at length in Voicetracks: Attuning to Voice in Media and the Arts. (shameless plug for my book, just out in May!) I’ll just grab an edited teaser from there for now: “Catherine Clover has been making works for and with noisy, wild urban birds for many years—listening, recording, translating, transcribing, reading to them, performing for and with and after them, making books and performances and installations. Like some of the scientists that Vinciane Despret discussed, Clover seeks artistic practices and ways to develop relationships of attunement with the birds. Her choice of urban gulls and pigeons is deliberately not sentimental; instead of ‘beautiful’ and mellifluous or even sublime birds, calling to us from the ‘wild,’ she works in a sort of minor mode with despised and everyday species. These are birds with whom we share urban space but often without noticing them, unless to bemoan their presence. These are birds whose groupings we name as deadly and dirty—a murder of crows, a filth of starlings, as the title of one of Clover’s works reminds me.”

I’m sure I’ll come back to Clover and Despret and of course to attunement – as well as to the can of worms that is becoming-animal — which I just wanted to open for now. Meanwhile, wriggling around in this can of worms has made we want to read Donna Haraway — Staying with the Trouble calls. While the worms are still in their wintry quietude, I’ll keep bookworming.

A few days ago, when I was ‘Taking a break,’ I was gripped by Adam Phillips’ essay on Darwin, worms, and digestion. When Phillips says Charles Darwin “commemorates, and rejoices in, the [worms’] powers of digestion” (55), I’m definitely in. Since then I too burrowed into the rich ground of Darwin’s The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Action of Worms.

It’s been quite an alchemical experience, as I burped my way through Darwin’s book (my gut telling me I’d had way too much coffee when I was trying to lure the worms out from under their blanket with ever more coffee grounds). The experience reminded me of when I was working on a radiophonic essay on alchemy and its transformations [Separation Anxiety: not the truth about alchemy]—and I went through all the seven stages of alchemy in the process. Dissolution was painful and the coagulation was intense, but it was putrefaction and fermentation that was the most challenging and transformative of all. Time for a new category for the blog — digestion.

I like that the worms call me to think about alchemy again now, years later. Alchemy is an alluring knowledge that is all about affinities and transformation… just like the project working with worms. It’s turning out that alchemical transformations and affinities abound once we tune in to them. Not just digestion – there is also shredding. We seem to be kindred Kin here, as Donna Haraway might have it… us with our shredding habit and the worms with theirs. (As I said in the early days of the blog, we shredded a lot of paper for a previous art work, and now we’re feeding the shreds to the worms to digest and transform. (Strangely, looking back, we actually did try to eat them ourselves in that work, but not too successfully– there were just way too many to digest.)

I’m inspired when Darwin speaks about the intimate co-compositional moments in shredding and digesting: “The leaves which they consume are moistened, torn into small shreds, partially digested, and intimately commingled with the earth…” (79) And so we feed the worms our shredded leaves of paper to do with what they will, to transform in their alchemical habitual way. There’s an unexpected intimacy here as we wait and wonder…

And thinking about wonder, when I was looking for what Jane Bennett said about alchemy in her wonderful The Enchantment of Modern Life, I remembered how important her work has been for us. It made me sense how enchanting the worms are in the work they are doing with us. Darwin, too, seems enchanted by worms and his amazement is infections. But, bowing to science, he also fills the book with calculations to demonstrate the power of worms. That I didn’t mind– they seemed to make him happy– but I have to say I did gasp as I read of the eviscerated worms sacrificed to science to explain the chemical functioning of their digestion. Sadly, it seems that quite a few worms suffered in the writing of that book, paying a price for the glory of worm-kind. At the same time, though, I feel drawn to the Darwin who is not bowed by science, who tells stories of running around old buildings with his sons and working at home observing the eating and burrowing habits of worms. And I laugh at the Darwin who gently blows tobacco breath at the worms as part of his enquiries into their senses. These passages where he speaks as a more attuned, amateur scientist, are for me far more alluring and thought-provoking than his descriptions of their dissected digestive tracts.

But I think I like Darwin best when he’s discussing the worms’ favourite foods. And the way he’s moved by their consciousness, their attentiveness, their intelligence and the sensitivity to touch of their whole bodies. And when he assures us how hugely important part a worms play in the history of the world. And when, asking what Vinciane Despret calls the ‘right questions,’ he is rewarded by the surprises of worms’ responses—as, for example, when together they bury the tired concept of blind instinct: “But it is far more surprising that they should apparently exhibit some degrees of intelligence instead of a mere blind instinctive impulse, in their manner of plugging up the mouths of their burrows.” (103)

What I’ve responded to in Darwin’s engaging worms is what Phillips calls his “artful science” (55). Like Despret I appreciate Darwin’s recognition of animals’ agency and aesthetic sense (37-38). This is a far cry from the scientists Despret questions for being out of touch with the affects and effects of their relations with the animals they study.

I’m happy to be coming back to Despret. I realise that I’ve digested about as much science of worms as I want to and it’s time to think about art again. So I return with relish to her artful writing and her first chapter (“A for artists”). Stirring words about the importance of the achievements as “beasts and humans accomplish a work together. And they do so with the grace and joy of the work to be done.” And so she finishes, “Isn’t this what matters in the end? To welcome new ways of speaking, describing, and narrating that allow us to respond, in a sensitive way to these events?” (6)

We went to see the film Kedi, the other day, following seven of the many cats that roam the streets of Istanbul. It was deeply moving and surprising and we’re still thinking about it. I know, this is supposed to be about worms, not cats, but like our companion cats, they help us think.

Kedi cats have so much to say about the city of Istanbul and its people and Islamic culture. They tell of relationships between people and animals and a city quite different from those in Australia, say, where cats are classified as either domesticated or feral.

Kedi cats invite us to think about how relationships of care and shared vulnerability can affectively and ethically connect us and other creatures. Anat Pick beautifully figures “creaturely vulnerability,” proposing that it is material obligations and shared bodily vulnerabilities that characterize the creaturely commonality and “point of encounter between human and animal” (Creaturely Poetics). What Kedi cats add to this story is that care does not need to be based on ownership and sentimentality.

I think this is part of the appeal of working with worms too. Yes, all paths do lead back to worms… One of the many allures of worms is that they evoke neither sentimentality nor a desire for ownership. As unexpected artful collaborators these vulnerable creatures demand different entanglements of care — that we haven’t worked out before — and that, in a way, our project together is about elaborating and thinking about.

Slowing right down, attuning in to the worms’ rhythm, I went for a morning wander by the Yarra River, thinking I might come across some other worms to bother with my camera. I started out listening to a program live on ABC radio which weirdly enough was all about slowness–the universe is definitely telling me something. As I crossed the pipe bridge, some walkers alerted me to a pair of mopokes in a nearby tree. What’s a mopoke, I wondered?

I only managed a couple of shaky distant pictures — but I’ll put them up so you can see the beautiful Yarra gum trees. It’s difficult to tell if they really are mopokes or boobooks as they also call and are also called. I hope so, I love these names– though they could be tawny frogmouths, also wonderfully named worm-eating owls (oops, sorry worms). A moment of enchantment, as Jane Bennett would have it, “intense enough to stop you in your tracks and toss you onto new terrain. (2001, 111)”

Stopped in my tracks, I’ve gone back to read the blog from the beginning and realise we haven’t really described the project that this blog is part of. Working with Worms is a collaborative, durational, art project where we feed the worms and they transform ‘dead’ matter into live soil. Where it will end, we don’t know, we have no specific expectations but there are a few wild dreams. Meanwhile we’re going with the flow of the project that entangles waiting, conversations, faeces, transformation, and environmental concerns. Waiting is fundamental to our process — just as it is an important part of many other artists’ practices – involving an attentiveness to time, to ‘silence,’ to process. It’s what artist Lyndal Jones calls a “becoming earth,” a responsiveness to the “insistences of the ground.” For us, it’s the insistences of the ground’s worms that we want to attend to. This is a project very much in progress, or rather very slowly in progress, it being winter and the worms taking their time as we’ve noted in previous posts. While they settle in, we’re being bookworm, reading and blogging– all of us working slowly and sporadically.